Introduction

Playing a musical instrument at a professional level requires many hours of daily practice, rehearsal, and experience of performing under concert conditions, which puts great demands on the musculoskeletal system of the musician (Wilke et al., 2011). The competitive environment of professional orchestral musicians further increases these demands which is thought to lead to a high prevalence of playing related musculoskeletal disorders (PRMD) (Ajidahun et al., 2019). Professional orchestral musicians are the elite of their occupation and the physical demands they are exposed to have previously been compared to the demands of top athletes and soldiers (Paarup et al., 2011; Quarrier, 1993). Estimations of exposure times are suggested to be about 1,300 hours per year (Paarup et al., 2011), with longest continuous active playing times at or above three hours per performance or rehearsal (Nyman et al., 2007). Thereby, all professional orchestral musicians need sufficient levels of strength, mobility, motor control, and muscular endurance to perform at the highest levels on a daily basis (Lundborg & Grooten, 2018). This is especially true for string players, as they are known to play the most notes for the longest durations in virtually all classical and modern orchestral compositions. String players are forced into a semi-static asymmetrical sitting position due to string specific playing technique (Wilke et al., 2011). Furthermore, the shoulder abduction with bent elbows to varying degrees in both arms leads to high shoulder moments and rotational torque of the humerus (Chaffin & Andersson, 1991). These technique related postural demands often lead to degenerative and overuse conditions, that manifest as musculoskeletal disorders which interfere with the playing technique mostly as a result of pain (Wilke et al., 2011). The umbrella term PRMD was introduced by Zaza (1998) and describes musculoskeletal conditions like pain, numbness, tingling, or weakness that interfere with the ability to play a musical instrument (Ackermann et al., 2002).

The 12-month prevalence of PRMDs among professional orchestral musicians is reported to be as high as 86% (Leaver et al., 2011), of which up to 68% are represented by string players (Violin, Viola, Cello, Double Bass) (Kaufman-Cohen & Ratzon, 2011). Of those string players effected by PRMDs, 59% are experiencing lower back pain, 55% neck pain, 55% shoulder pain, 23% elbow pain, and 32% hand and wrist pain (Leaver et al., 2011). As the discomfort, particularly caused by the pain aspect of PRMDs is affecting the stress levels of the musician, the musical performance, expressiveness, and enjoyment of playing is negatively impacted by PRMDs (Guptill, 2012). The physical, psychological, and socio-economic impacts of PRMDs can be career altering or even career ending for the players (Kaufman-Cohen & Ratzon, 2011; Spahn et al., 2001; Zaza, 1998), and is causing additional costs for orchestras to pay for sick leave and to provide for substitute players (Steinmetz et al., 2015). Multiple strategies have been proposed to ameliorate the effects of PRMDs among musicians, ranging from an emphasis on technical correct sitting and holding the instrument, correct setup of the instrument (Butler & Norris, 2011), inclusion of warmup exercises (Frederickson, 2002), and different forms of preventative exercising (Ackermann et al., 2002; Kroll, 2015; Lundborg & Grooten, 2018) or physiotherapy (Chan & Ackermann, 2014). Generally, the high prevalence of PRMDs among string players could indicate a relatively low capacity to tolerate the impact of playing (Steinmetz et al., 2010), thus training strategies that increase certain physical capacities could lead to improved stress tolerance of the musculoskeletal system, relative load reduction, and increased reserve capacity (Sundstrup et al., 2016).

Specifically, the capacity to express sufficient levels of muscular endurance for the muscles responsible for postural control of the upper body and shoulders seem to influence the levels of musculoskeletal disorders, as shown in the field of occupational health (Chopp-Hurley et al., 2016). For example, the muscular endurance levels of the intrinsic musculature of the shoulder (Serratus anterior, Trapezius pars ascendens, Rhomboids) have a strong correlation with non-specific shoulder pain in the general working population (Evans et al., 2021). The same correlation was found between the muscular endurance of the lumbar trunk muscles and lower back pain in working populations who are exposed to extended times of sitting and physical inactivity (O’Sullivan et al., 2006). Similar to that, the same correlation appears also in neck pain sufferers who show insufficient levels of muscular endurance of the neck musculature (Reddy et al., 2021). However, it is noteworthy to point out that PRMDs are different from chronic pain as they only occur during periods of prolonged playing, although in some cases it might be that chronic pain coincides with PRMDs during playing, which would lead to a worsening and or spreading of pain. The mechanisms of (non-specific) pain generation are plentiful, hard to diagnose and the current understanding is limited (Allegri et al., 2016). The underlying mechanisms are proposed to be the complex interaction of nociceptive inputs, and endogenous modulatory systems of the peripheral and central nervous system (Kroll, 2015). Some of these pain inputs are likely to be caused by inflammatory and degenerative processes caused by overuse and inadequate posture (Allegri et al., 2016). It is unclear if the positive effect of some forms of exercise is the result of adaptations of muscle/tendon function or because of changes in the pain modulatory system of the nervous system, as in some cases improvements of pain levels do not associate with improved muscle function (Mannion et al., 2012). However, as mentioned above, there seems to be a correlation between muscular endurance levels and pain levels in several papers (Allegri et al., 2016; Evans et al., 2021; Kroll, 2015; O’Sullivan et al., 2006; Reddy et al., 2021). Muscular endurance as defined by Bäckman (1995) is the ability of the muscle to produce force over extended periods of time or multiple repetitions of a submaximal load.

Considering that the postural work of string players over extended periods of time represents a substantial challenge for the endurance of the musculature involved in postural control, and the fact that poor muscular endurance can lead to non-specific pain, it can be assumed that improved muscular endurance will have a positive effect on PRMDs among professional string players. Hence, it is hypothesised that an improvement of muscular endurance through an intervention that targets the most affected body parts (neck, shoulders, and back) will lead to a significant reduction in PRMDs among professional string players and measurable improvements of muscular endurance. Previous studies on a population of orchestral musicians have investigated the effect of specific strength training (L. N. Andersen et al., 2017), different warmup protocols (McCrary et al., 2016), flexibility and mobility (Cooper et al., 2012), yogic breathing (Lee et al., 2012), cardiovascular endurance training (Ackermann et al., 2002), and education on injury prevention (Spahn et al., 2017). Some of these were conducted only on music students and none have explored the effect of improved muscular endurance with high training volumes on (generally older) professional players. To the knowledge of this author there are very few (Ackermann et al., 2002; Kava et al., 2010) high-quality trials that investigate the aspect of improved muscular endurance of the upper body and its effect on PRMDs among professional string players. The aim of this study is to investigate the effect of improved muscular endurance on PRMDs in professional string players and to evaluate if an increase of muscular endurance is indeed causal to a reduction of PRMDs. To this point it is unclear if such intervention would influence muscular endurance levels alone, PRMD levels alone, or both at the same time.

Methods

Study design

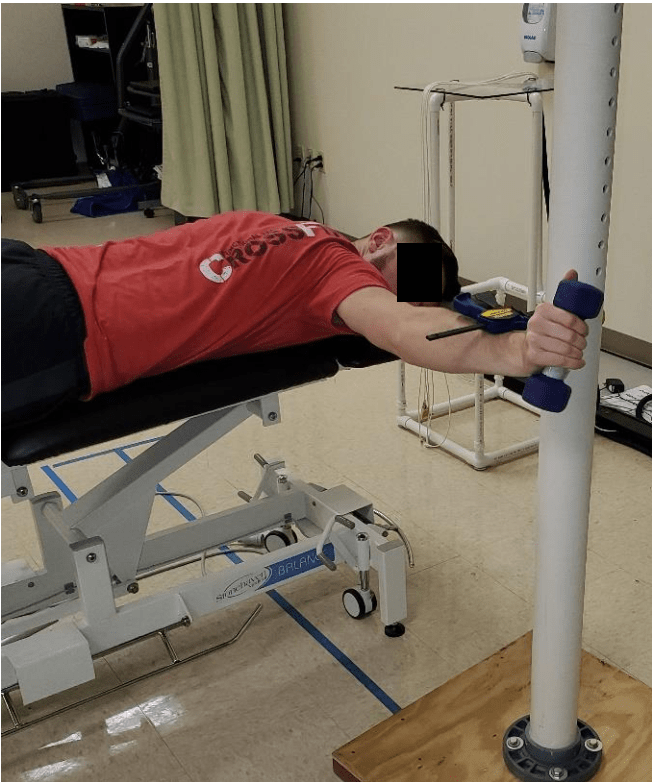

This prospective randomised controlled trial is a 6-week intervention study that will investigate the effect of increased muscular endurance on PRMDs among professional string players. After enrolling into the study, the participants will be block randomised by gender into either the intervention or the control group. All participants will perform a pre-test to establish the baseline PRMD levels (self-reported questionnaire based on VAS 0-10 / 0 – 100) and time to failure (TTF) in seconds for the prone scapula endurance test (PSET) at 90 degrees horizontal shoulder abduction (Evans et al., 2018). The participants of the intervention group will follow a professionally guided training programme in a home workout setting via remote coaching (ZOOM). There will be 3 weekly sessions of 20 to 30 minutes of guided exercise following the study exercise plan (Figure 3). The control group is encouraged to stay physically active but does not receive any coaching. After 6 weeks the muscular endurance levels of both groups are tested for the second time during the PSET. The participants of both arms of the study are answering a bi-weekly online based questionnaire over the period of the trial (4 in total, 1 pre-test, 1 after 2 weeks, 1 after 4 weeks, 1 post-test). Both groups report their frequency of PRMDs on a visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0 – 10, severity of PRMDs on a visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0 – 100, and rates of perceived exhaustion during playing on a Borg scale (Borg) from 6 to 20. Additional questions serve to gather data for control purposes. This study will follow international ethics guidelines and has been agreed upon by the institutional board of St Marys University London Twickenham on the 12th of December 2022. All participants are informed regarding possible effects (training related muscle soreness, improved muscular endurance) and will give their consent in writing before the start of the study.

Participants

For this study 25 professional string players who are full-time freelancers for-, or full-time members of national level orchestras from across the UK are going to be recruited. All participants enrolled in the study have current experiences with PRMDs. Because of the level of professional experience of the enrolled string players in this study, the average age likely to fall within the middle age to older age bracket (40 – 60+ years). The distribution between genders within the sampled group is likely to be the same as of the general population of professional string players (40% male, 60% female). Exclusion criteria are candidates who are known migraineurs as muscular endurance training of the neck can trigger the condition (Carvalho et al., 2021), players with PRMDs who have undergone treatments like surgery on back, neck or shoulder, individuals that are habitually taking part in ongoing training activities with the same aim as the intervention arm of this trial. To save guard the participants, players who are currently on sick leave because of musculoskeletal conditions are also excluded from the study.

Statistics and data handling

An independent t-test will be performed on the means of both groups for TTF (seconds) of PSET results before and after the intervention (Evans et al., 2018). A repeated measures analysis of variances (ANOVA) with post-hoc test for the self-reported PRMD severity and frequency, rate of perceived exhaustion (RPE) during playing and several control questions (as time-varying covariates) from the bi-weekly questionnaires is being performed. The power analysis for the repeated measures ANOVA was performed prior to the investigation, which gave a sample size of 25 participants (including 10% loss to follow up) to reject the null hypothesis of equality for a statistical power of 90%, p=0.05 to detect a clinically significant change in pain of 15 (Kovacs et al., 2008) on a 0 – 100 scale between groups based on the ratings of pain severity (C. H. Andersen et al., 2014), with an effect size of 0.88. The power analysis for the one-tailed independent t-test was performed prior to the investigation, which gave a sample size of 25 participants (including 10% loss to follow up) to reject the null hypothesis of equality for a statistical power of 70%, p=0.05 to detect an effect size of 1.0 of TTF performance in the PSET between both groups at the pre- and post-test. The primary outcome measures are the severity and frequency of PRMDs recorded from the bi-weekly questionnaires on a scale from 0 – 100 and 0 – 10 respectively (dependant variable). The secondary outcome measure is the TTF in seconds recorded during the PSET (dependant variable) (Evans et al., 2018). The independent variables are the completed weekly exercise volume and the holding time of the prone position in seconds derived from volume and exercise speed in repetitions per minute. Additional control variables like time to resolving PRMDs after playing, RPE after actively playing the instrument, frequency and severity of chronic non-specific pain, number of weekly hours of active playing the instrument, number of weekly hours of exercising outside the trial, and usual RPE after exercise outside the trial are being derived from the questionnaires. All questionnaire data will be collected via internet forms or during testing on site, prepared in long form in Microsoft Excel (365), and the statistical analysis will be performed with the current version of IBM’s SPSS statistical software.

Test procedure

The prone scapular endurance test (PSET) was originally described by Moore et al. (2013) as an isotonic test performed in prone position while lifting the arm to 90 degree of horizontal shoulder abduction at a rate of 30 beats per minute, and was later modified to be isometric by Day et al. (2015), and validated multiple times by Evans (Evans et al., 2018, 2021). The dominant arm is used during testing. The length of the dominant arm is measured from the acromioclavicular joint to the distal end of the radial styloid process with the elbow straight. Body weight is measured with the help of a conventional digital body scale. With the measured body weight and arm length the external torque of the shoulder is calculated (Figure 2). The nominal torque levels are standardised to the 50th percentile of published anthropometric data for males (21 ±1 Nm) and females(13 ±1 Nm) (Chaffin & Andersson, 1991; Evans et al., 2021). After the shoulder torque provided by the arm alone is calculated, the necessary external load is calculated to make up to the nominal torque levels for testing (to the closest increment of the weight set utilised) (Evans et al., 2021). All test subjects are completing a standardised 10-minute warmup programme before the test procedure begins. There will be a 48-to-72-hour recovery period before the pre-test to allow for enough recovery for the members of the intervention group. The test subject in prone position (on a horizontal bench or treatment table) will hold the arm plus the external load, with the arm externally rotated and in horizontal abduction at a shoulder angle of 90 degrees for as long as possible (Figure 1). To ensure correct form, the arm is held at wrist height against a standalone target and the failure to maintain this position for any reason will end the test and stop the clock (Evans et al., 2021). During the test procedure the subject will receive verbal encouragement to continue (Evans et al., 2021). The resulting time (in seconds) will be written down on paper and additionally entered into an Excel spreadsheet for later data processing and analysis. The questionnaires are being completed to evaluate pain levels / PRMD severity and frequency. The questionnaires are being handed out and returned electronically via the internet (Google Forms or PFD).

Study training plan

Over the 6-week training period the participants will take part in 3 weekly training sessions of 20 to 30 minutes per session. All sessions will start with a 5-to-10-minute warmup. Over the course of these 18 sessions, the participants will follow a training plan of progressively increased exercise volume, with 48 to 72 hours between workouts to allow for appropriate recovery. Significant improvements in muscular endurance of the upper body have been observed using between 15 and 24 repetitions per set (Hackett et al., 2022), with no benefit beyond 5 sets per workout (Hackett et al., 2021; Radaelli et al., 2015). Hence, the progression of the study training plan (Figure 3) aims to reach 5 sets of 25 reps for the last 2 weeks of the intervention. All sets are using submaximal external loads that are matched to ensure near monetary muscle failure at the end of each set. The exercises are designed to target the posterior musculature of the trunk (isometrically), shoulder (isotonically), and neck (isometrically). During the workout all exercise repetitions are being performed at a speed of 30 repetitions per minute with the help of a metronome. Where applicable, the exercises are performed free standing with free weights. The main exercises are the standing prone position reverse fly’s (Figure 4), the standing prone position shoulder flexion to the front (Figure 5), and the standing prone position shoulder hyper extension (Figure 6). During the early sessions in the first weeks, special focus will be put on correct execution of the movements, shoulder blade positioning, and neutral position of the back and neck (cues: chest up, shoulders back and down, chin in, stick the bum out to the back).

Timeline

After the ethics approval of the institutional board in October 2022 the recruitment process starts in November 2022. Twenty-five professional string players from national level orchestras in the UK are being recruited and the pre-test is conducted via ZOOM at the beginning of January 2023. At the latest in mid-January the training programme for the intervention group will start. All 18 of the 30-minute training sessions are being conducted remotely via ZOOM, if possible as a group, to make the intervention feasible and fit in with the already very busy schedule of a professional musician and the researcher. After the intervention period at the end of February the post test will be conducted. Both study groups are answering the pain questionnaire before the pre-test, after 2 weeks of the intervention, after 4 weeks of the intervention, and after the intervention before the post-test. The collected data will be processed during the first weeks of March and the results written up to be handed in for peer review and final marking in April / June. The author aims to publish the results of this study in the journal “Medical Problems of Performing Artists” (MPPA, n.d.).

Finances

This study is designed to be as cost effective as possible. The interaction with the participants during the trial is mainly conducted remotely which minimises the need for time and energy costs of travel and transportation. Under certain circumstances even the testing procedure could be done without person-to-person interaction, which is a contingency measure in case of unexpected public health emergency measures put in place by governing bodies. The testing procedure requires the following materials: 1 bench or massage table, 1 small set of dumbbells (250g increments) or personalised weights (sandbags filled according to calculation), 1 stopwatch (Hanhart, Stopstar 2), 1 pocket calculator, 1 pair of locking pliers, 1 free standing target, 1 tape measure, 1 pack of antibacterial wipes, 1 pen, 1 small notebook, 1 roll of sticky tape, 2m of paracord, and 1 sharpie.

Figures

Figure 1:

Prone position scapular endurance test (PSET) configuration

(Evans et al., 2021)

Figures 2 to 6 have been removed from the blog article version of this proposal.

References

Ackermann, B., Adams, R., & Marshall, E. (2002). Strength or endurance training for undergraduate music majors at a university? Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 17, 33–41.

Ajidahun, A., Myezwa, H., Mudzi, W., & Wood, W.-A. (2019). A Scoping Review of Exercise Intervention for Playing- Related Musculoskeletal Disorders (PRMDs) among Musicians. Muziki, 16, 1–24.

Allegri, M., Montella, S., Salici, F., Valente, A., Marchesini, M., Compagnone, C., Baciarello, M., Manferdini, M. E., & Fanelli, G. (2016). Mechanisms of low back pain: A guide for diagnosis and therapy. F1000Research, 5.

Andersen, C. H., Andersen, L. L., Zebis, M. K., & Sjøgaard, G. (2014). Effect of scapular function training on chronic pain in the neck/shoulder region: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 24, 316–324.

Andersen, L. N., Mann, S., Juul-Kristensen, B., & Søgaard, K. (2017). Comparing the Impact of Specific Strength Training vs General Fitness Training on Professional Symphony Orchestra Musicians: A Feasibility Study. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 32, 94–100.

Bäckman, E., Johansson, V., Häger, B., Sjöblom, P., & Henriksson, K. G. (1995). Isometric muscle strength and muscular endurance in normal persons aged between 17 and 70 years. Scandinavian Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 27, 109–117.

Borg, G. (1998). Borg’s perceived exertion and pain scales. Human kinetics.

Butler, K., & Norris, R. (2011). Assessment and treatment principles for the upper limb of instrumental musicians. (pp. 1855–1878).

Carvalho, G. F., Luedtke, K., Szikszay, T. M., Bevilaqua-Grossi, D., & May, A. (2021). Muscle endurance training of the neck triggers migraine attacks. Cephalalgia, 41, 383–391.

Chaffin, D. B., & Andersson, G. B. (1991). Occupational Biomechanics (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Chan, C., & Ackermann, B. (2014). Evidence-informed physical therapy management of performance-related musculoskeletal disorders in musicians. Frontiers in Psychology, 5.

Chopp-Hurley, J. N., O’Neill, J. M., McDonald, A. C., Maciukiewicz, J. M., & Dickerson, C. R. (2016). Fatigue-induced glenohumeral and scapulothoracic kinematic variability: Implications for subacromial space reduction. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 29, 55–63.

Clauser, C. E., McConville, J. T., & Young, J. W. (1969). Weight, volume, and center of mass of segments of the human body. Antioch Coll Yellow Springs OH.

Cooper, S. C., Hamann, D. L., & Frost, R. (2012). The effects of stretching exercises during rehearsals on string students’ self-reported perceptions of discomfort. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 30, 71–76.

Day, J. M., Bush, H., Nitz, A. J., & Uhl, T. L. (2015). Scapular muscle performance in individuals with lateral epicondylalgia. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 45, 414–424.

Evans, N. A., Dressler, E., & Uhl, T. (2018). An electromyography study of muscular endurance during the posterior shoulder endurance test. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 41, 132–138.

Evans, N. A., Konz, S., Nitz, A., & Uhl, T. L. (2021). Reproducibility and discriminant validity of the Posterior Shoulder Endurance Test in healthy and painful populations. Physical Therapy in Sport, 47, 66–71.

Frederickson, K. B. (2002). Fit to play: Musicians’ health tips. Music Educators Journal, 88, 38–44.

Guptill, C. (2012). Injured professional musicians and the complex relationship between occupation and health. Journal of Occupational Science, 19, 258–270.

Hackett, D. A., Davies, T. B., & Sabag, A. (2021). Effect of 10 sets versus 5 sets of resistance training on muscular endurance. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 62, 778–787.

Hackett, D. A., Ghayomzadeh, M., Farrell, S. N., Davies, T. B., & Sabag, A. (2022). Influence of total repetitions per set on local muscular endurance: A systematic review with meta-analysis and meta-regression. Science & Sports, 37, 405–420.

Kaufman-Cohen, Y., & Ratzon, N. Z. (2011). Correlation between risk factors and musculoskeletal disorders among classical musicians. Occupational Medicine, 61, 90–95.

Kava, K. S., Larson, C. A., Stiller, C. H., & Maher, S. F. (2010). Trunk endurance exercise and the effect on instrumental performance: A preliminary study comparing Pilates exercise and a trunk and proximal upper extremity endurance exercise program. Music Performance Research, 3, 1–30.

Kovacs, F. M., Abraira, V., Royuela, A., Corcoll, J., Alegre, L., Tomás, M., Mir, M. A., Cano, A., Muriel, A., & Zamora, J. (2008). Minimum detectable and minimal clinically important changes for pain in patients with nonspecific neck pain. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 9, 1–9.

Kroll, H. R. (2015). Exercise therapy for chronic pain. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics, 26, 263–281.

Leaver, R., Harris, E. C., & Palmer, K. T. (2011). Musculoskeletal pain in elite professional musicians from British symphony orchestras. Occupational Medicine, 61, 549–555.

Lee, S.-H., Carey, S., Dubey, R., & Matz, R. (2012). Intervention program in college instrumental musicians, with kinematics analysis of cello and flute playing: A combined program of yogic breathing and muscle strengthening-flexibility exercises. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 27, 85–94.

Lundborg, B., & Grooten, W. J. (2018). Resistance training for professional string musicians: A prospective intervention study. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 33, 102–110.

Mannion, A. F., Caporaso, F., Pulkovski, N., & Sprott, H. (2012). Spine stabilisation exercises in the treatment of chronic low back pain: A good clinical outcome is not associated with improved abdominal muscle function. European Spine Journal, 21, 1301–1310.

McCrary, J. M., Halaki, M., Sorkin, E., & Ackermann, B. J. (2016). Acute warm-up effects in submaximal athletes: An EMG study of skilled violinists. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 48, 307–315.

Moore, S. D., Uhl, T. L., & Kibler, W. B. (2013). Improvements in shoulder endurance following a baseball-specific strengthening program in high school baseball players. Sports Health, 5, 233–238.

MPPA. (n.d.). Science & Medicine. Retrieved 6 September 2022, from https://www.sciandmed.com/mppa

Nyman, T., Wiktorin, C., Mulder, M., & Johansson, Y. L. (2007). Work postures and neck–shoulder pain among orchestra musicians. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 50, 370–376.

O’Sullivan, P. B., Mitchell, T., Bulich, P., Waller, R., & Holte, J. (2006). The relationship beween posture and back muscle endurance in industrial workers with flexion-related low back pain. Manual Therapy, 11, 264–271.

Paarup, H. M., Baelum, J., Holm, J. W., Manniche, C., & Wedderkopp, N. (2011). Prevalence and consequences of musculoskeletal symptoms in symphony orchestra musicians vary by gender: A cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 12, 1–14.

Quarrier, N. F. (1993). Performing arts medicine: The musical athlete. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 17, 90–95.

Radaelli, R., Fleck, S. J., Leite, T., Leite, R. D., Pinto, R. S., Fernandes, L., & Simão, R. (2015). Dose-response of 1, 3, and 5 sets of resistance exercise on strength, local muscular endurance, and hypertrophy. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 29, 1349–1358.

Reddy, R. S., Meziat-Filho, N., Ferreira, A. S., Tedla, J. S., Kandakurti, P. K., & Kakaraparthi, V. N. (2021). Comparison of neck extensor muscle endurance and cervical proprioception between asymptomatic individuals and patients with chronic neck pain. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 26, 180–186.

Spahn, C., Hildebrandt, H., & Seidenglanz, K. (2001). Effectiveness of a Prophylactic Course to Prevent Playing-related Health Problems of Music Students. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 16(1), 24–31.

Spahn, C., Voltmer, E., Mornell, A., & Nusseck, M. (2017). Health status and preventive health behavior of music students during university education: Merging prior results with new insights from a German multicenter study. Musicae Scientiae, 21, 213–229.

Steinmetz, A., Scheffer, I., Esmer, E., Delank, K. S., & Peroz, I. (2015). Frequency, severity and predictors of playing-related musculoskeletal pain in professional orchestral musicians in Germany. Clinical Rheumatology, 34, 965–973.

Steinmetz, A., Seidel, W., & Muche, B. (2010). Impairment of postural stabilization systems in musicians with playing-related musculoskeletal disorders. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, 33, 603–611.

Sundstrup, E., Jakobsen, M. D., Brandt, M., Jay, K., Aagaard, P., & Andersen, L. L. (2016). Strength training improves fatigue resistance and self-rated health in workers with chronic pain: A randomized controlled trial. BioMed Research International, 2016, 11.

Wilke, C., Priebus, J., Biallas, B., & Froböse, I. (2011). Motor activity as a way of preventing musculoskeletal problems in string musicians. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 26, 24–29.

Zaza, C. (1998). Playing-related musculoskeletal disorders in musicians: A systematic review of incidence and prevalence. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal, 158, 1019.

Zaza, C., Charles, C., & Muszynski, A. (1998). The meaning of playing-related musculoskeletal disorders to classical musicians. Social Science & Medicine, 47, 2013–2023.